Challenge

We were approached by a large financial services company who had recently opened an R&D office to help them build a product to benefit people who had little financial literacy but a desire to learn. In user interviews, people often mentioned never having learned about personal finance either from their parents or in school and being unable to pass on that vital knowledge to their own children. This inspired our problem statement: how might we provide tools at an early age instill financial confidence in adulthood, thereby ending the cycle of not belonging at the investment table?

Solution

Part of our task was to coach the team on how to create an innovative product, so as we worked, we walked them through the process of concepting, user research, rapid prototyping, testing and iterating. Our vision for a solution was a digital platform for both parents and kids that set them up for future financial success. It would do this by educating children through play and activities, while empowering parents with the knowledge they needed to support those activities.

Research

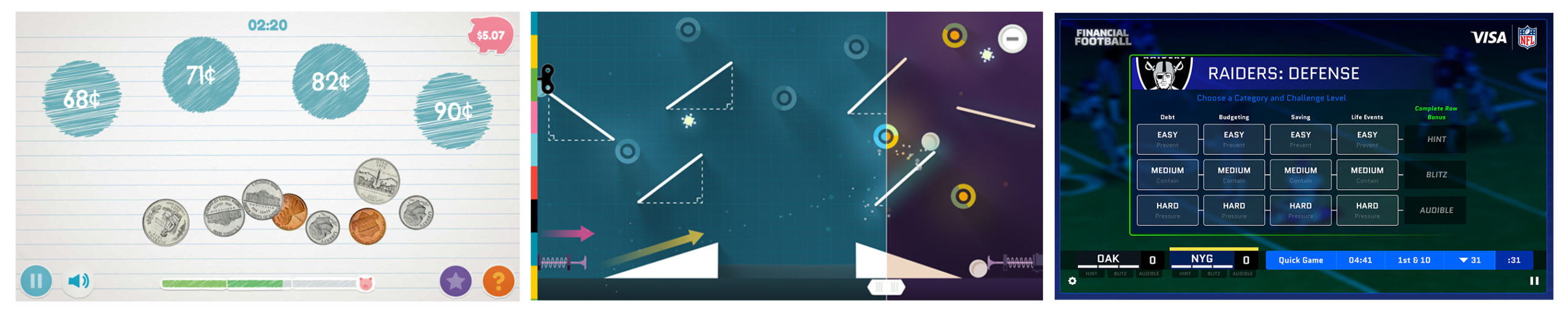

The first challenge was that I didn’t know any children and didn’t know anything about them. How do they learn? What do they do in their spare time? Do they know what money is? I completed competitive audit of games for kids, with a focus on the financial space. There were apps related to money management (such as managing your allowance) and educational games with financial content. The educational component was often presented in an expository way, out-of-context, the information shoehorned into the gameplay, making it nearly impossible to absorb. In addition, kids’ financial apps tended to suffer from uninspired design and poor usability. The unique ways kids think and use technology (exploration and discovery) was not reflected in the UX.

On the other hand, I really loved TocaBoca and Tinybop’s apps. Their design was kid-focused but beautiful, charming and delightful. I was sure that a visually stunning app which drew inspiration from outside the tech space (such as retro children’s games and books) and was truly designed for kids would go a long way in creating a meaningful and engaging experience.

We also did research into cognitive factors for kids, which informed our target age range. According to the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, 6 to 12 is the ideal age for absorbing the necessary skills and the time when financial habits and norms begin to form. We narrowed this down further to a range of 8 to 10, when kids begin to have a grasp of basic math, delayed gratification and app usage.

Ready, Set, Workshop

At this point, we did a two day workshop with the client team to quickly come to a consensus on what we wanted to build and test for an MVP, and to give them a brief look into our process.

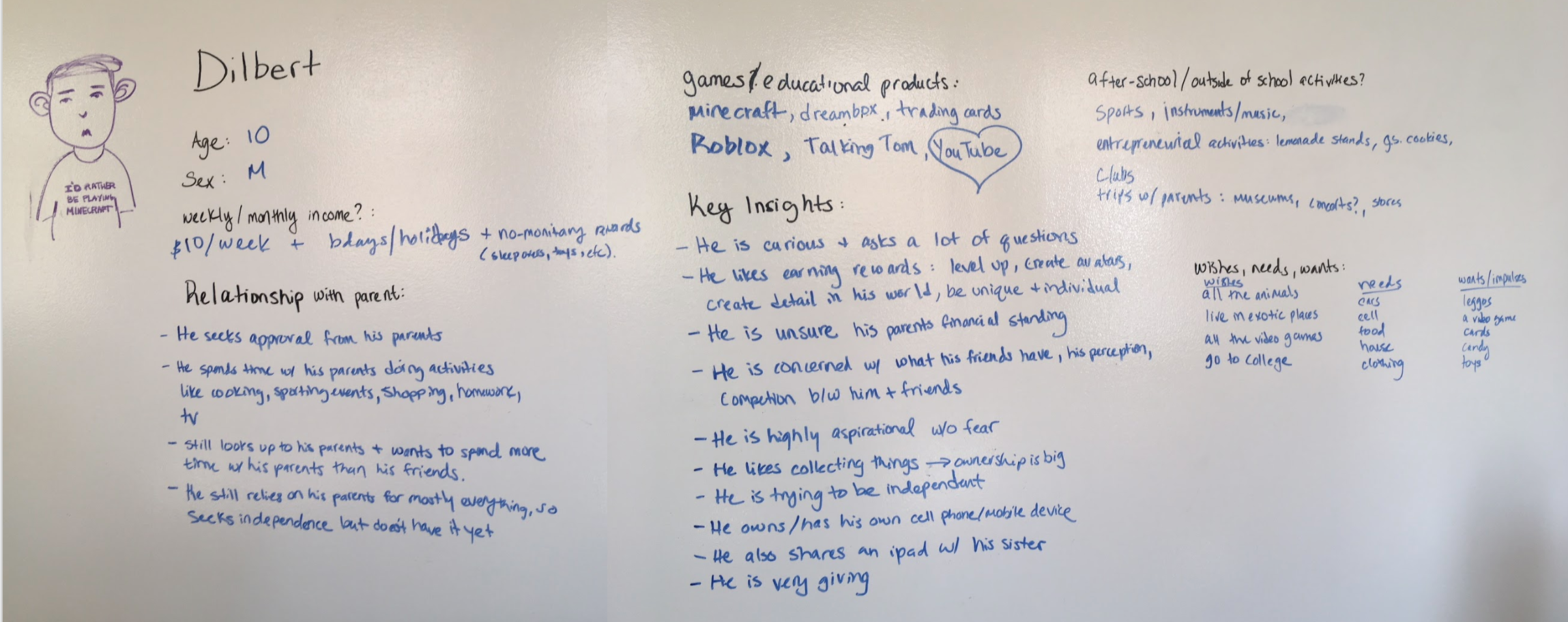

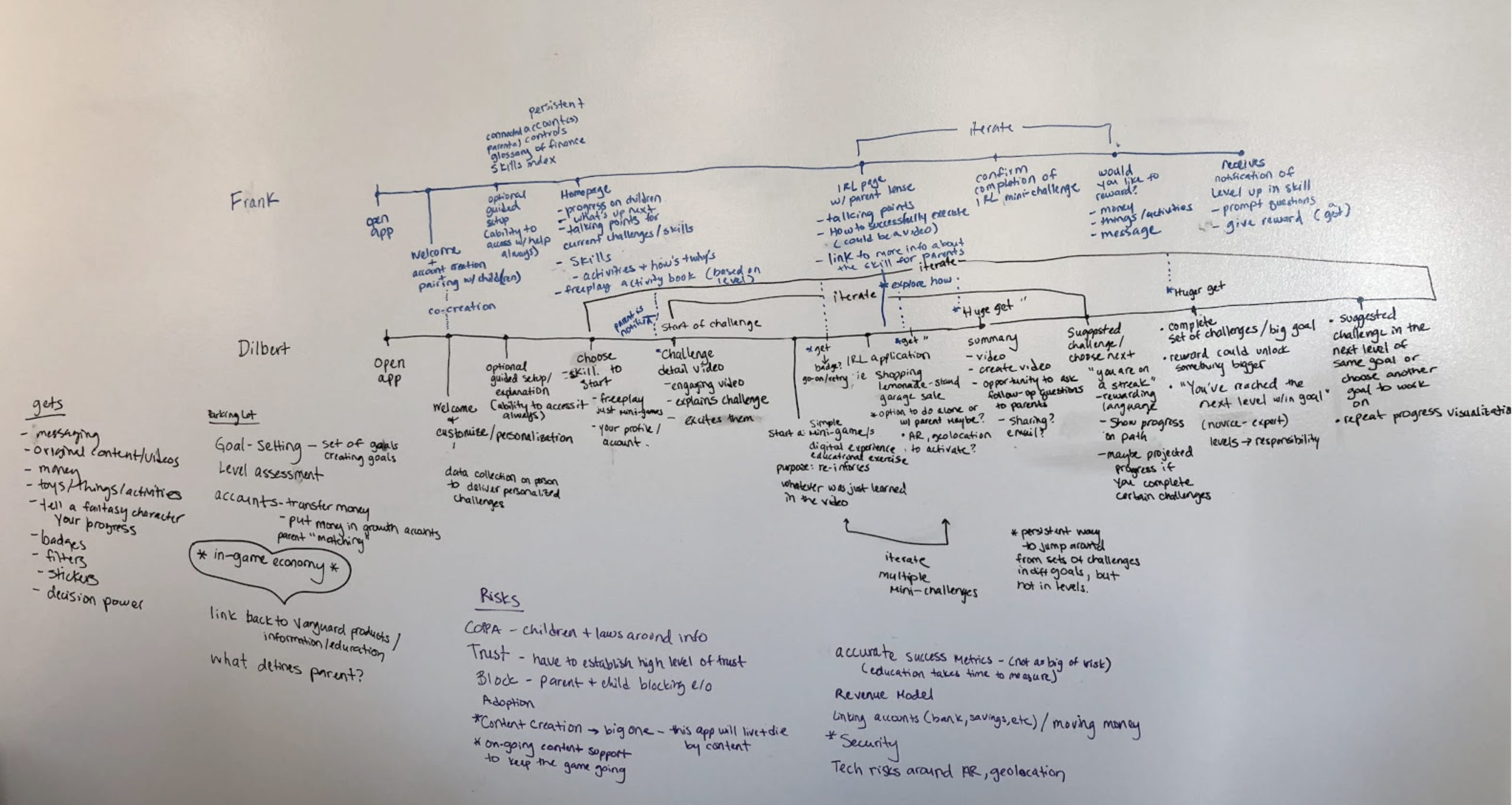

During the workshop, we put together assumptive personas for both the parents and the kids, based on our research and existing knowledge. Then, the team brainstormed game and activity concepts, coming up with a number of ideas that fit our criteria and could be placed along a spectrum between “educational with game components” and “game with educational components”. We assessed the pros and cons and decided on Badge Battle, in which kids choose a concept to focus on each week and complete both in-game and real world challenges alongside their parents.

Then, we worked together to define a basic flow for our MVP:

- Where does their experience begin and end?

- What tasks and decision points exist?

- What pages need to exist?

- What information needs to be presented?

Mo Concepts, Mo Problems

What emerged was a game concept in which kids travelled through the world of Pygglandia, leveling up their financial know-how through mini-games, with each game followed by a reward to keep the player motivated.

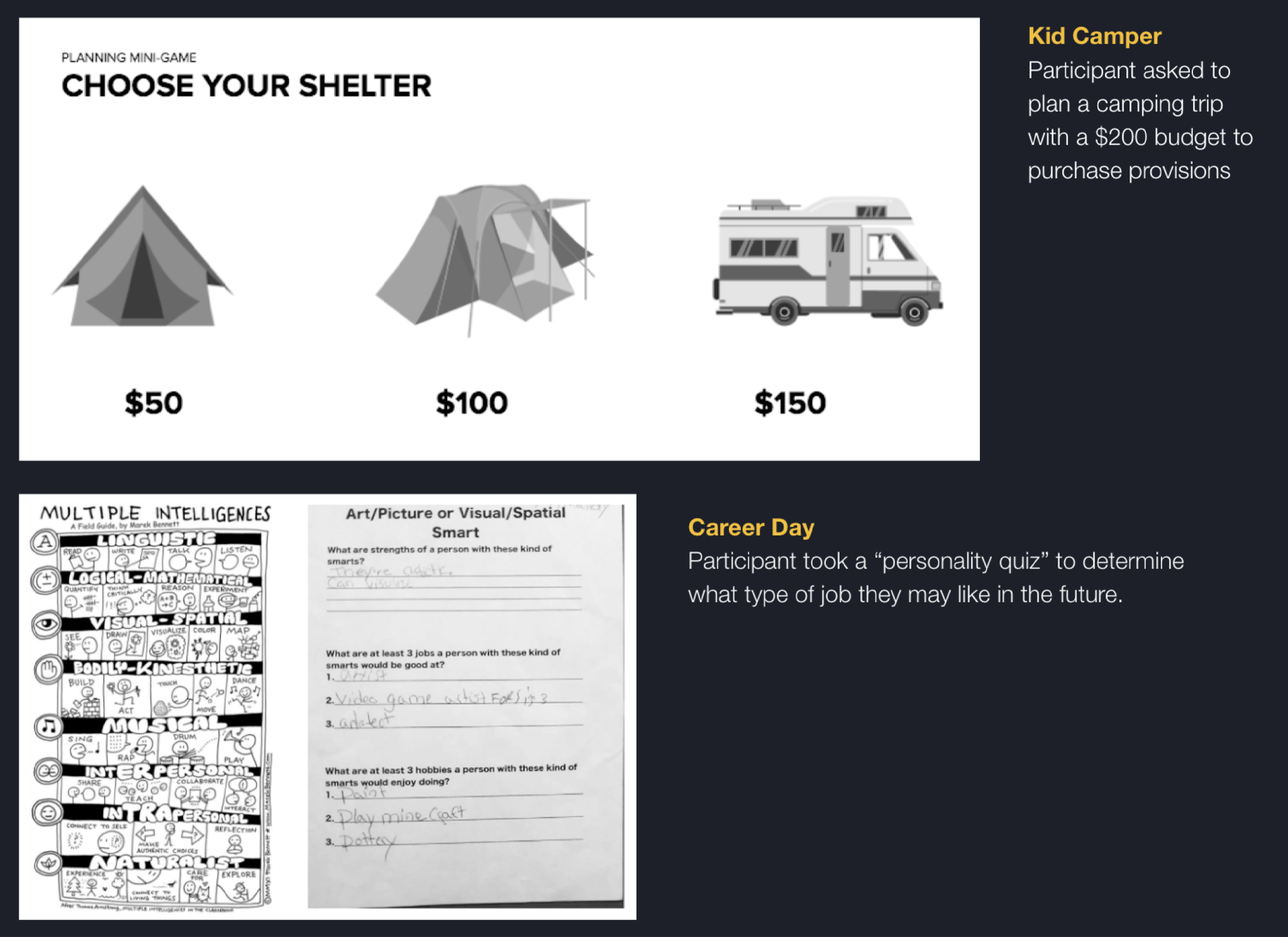

A product manager and researcher from the client team then put together a couple of mini games in order to concept test the idea of a game. Unfortunately, these mini-games had a few shortcomings that prevented us from getting clear and actionable results during testing. Ideally, we would have consulted a childhood education expert to help us craft a game that would be both interesting and educational. In addition, a lightweight or manual prototype that leaves off color, action, sound – the polish that makes an activity interesting to children – might not be appealing enough to get results.

Since we didn’t have the time or budget to hire educational consultants or beef up our prototype, we decided to revisit the research on how children learn and figure out a way we could effectively test the educational game concept given our restrictions.

The research noted that empowering kids to navigate realistic situations with realistic outcomes can help teach healthy habits. Instead of leaning too heavily into gaming (which was outside our area of expertise and restrictions), we shifted to a more activity-based approach. We came up with two activities to concept test.

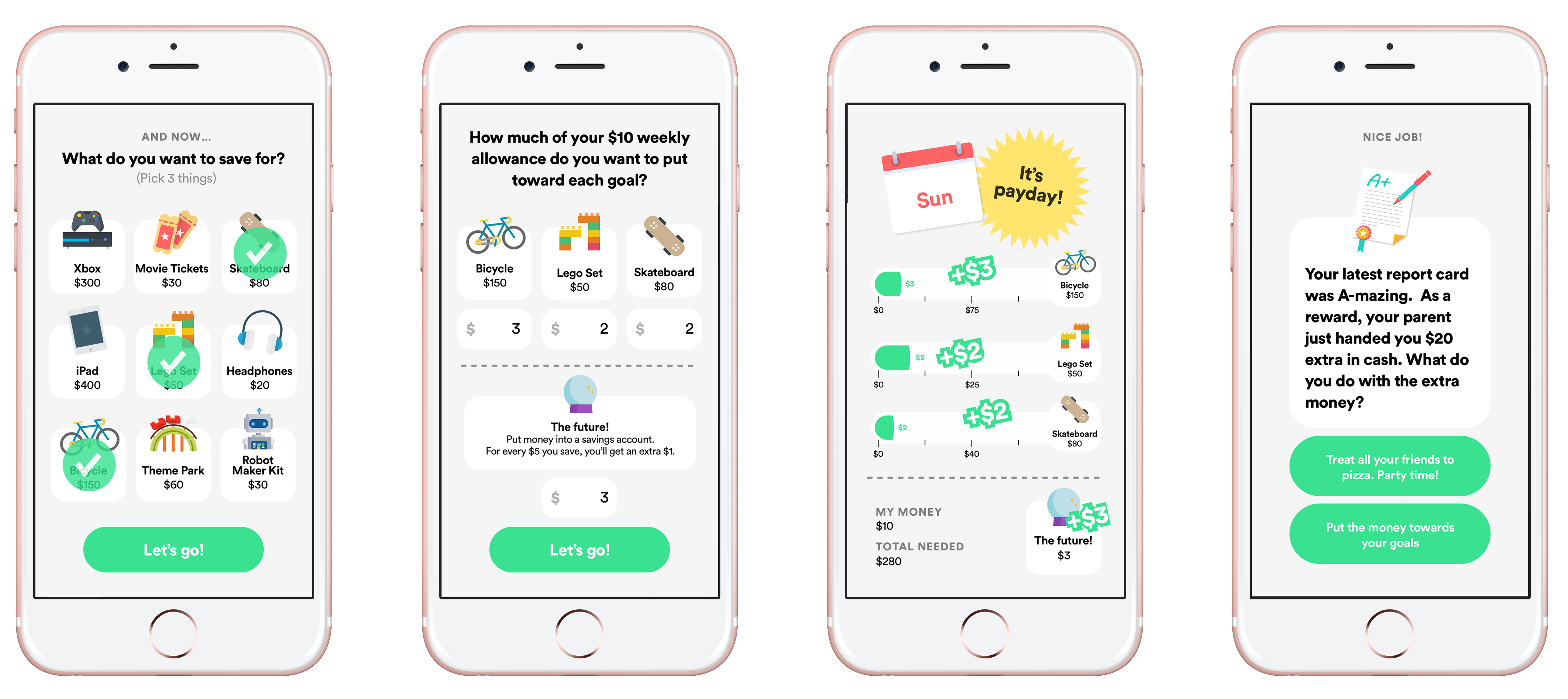

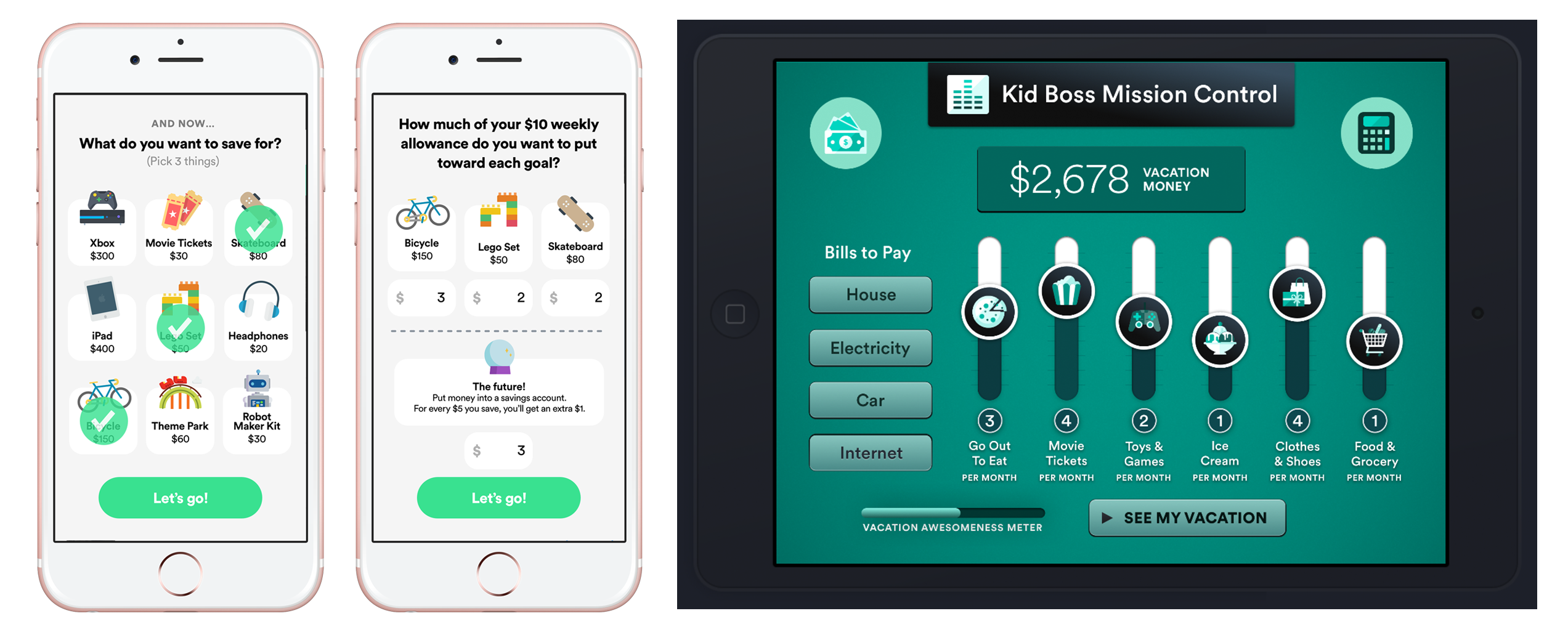

In the first activity, the kid receives a weekly allowance, picks savings goals, and distributes their allowance in a way that demonstrates how the process of saving and spending worked and the consequences of their financial decisions on their future. Click to see an Invision prototype of this activity.

In the second activity, kids are in their parents’ shoes and shown a mission control center in which they adjust their family’s financial flow (income, bills, ice cream) and see for themselves how that affects their ability to save for a family vacation.

Testing & Learning

TWe wanted to learn two things. First, which concept would best resonate with, and educate, kids: a parent-relevant activity (managing household finances) or a kid-relevant one (managing allowance money)? And second, would a big-goal activity (save for a family vacation) or a smaller-goal activity (save for movie tickets) be more effective?

We tested the concepts with four kids in our target age range and gained a lot of understanding about how they think about money:

- The concept of “The Future” and saving for something that may or may not happen, or even for long term goals, is intangible to kids and therefore not very motivating.

- Money transparency is important. When kids understand their parents’ financial concerns, their empathy increases. Giving kids the understand and decision-making power also increases their pride and self-reflection.

- Giving kids a space to practice and play with money in a safe environment, without fear of consequences, builds confidence that they can make positive financial decisions in the real world.

At this point our contract with the client came to an end. If it hadn’t, we would have explored how to layer on a parent experience to complement the child experience, as well as business case directions (after all, even R&D has to make money eventually).

In addition to my insight about the learning habits of children, I also learned a lot about working with the R&D lab of a large corporation. The most important lesson was that if leadership isn’t aligned with the parent company on R&D’s reason for existing, nothing will get done. Also that innovation isn’t a metric, it’s a byproduct of a thoughtful design process. And lastly, that if you went somewhere to teach and to learn, and you did just that, regardless of whether you shipped a product or not, you can consider the mission a success.